3

Feb

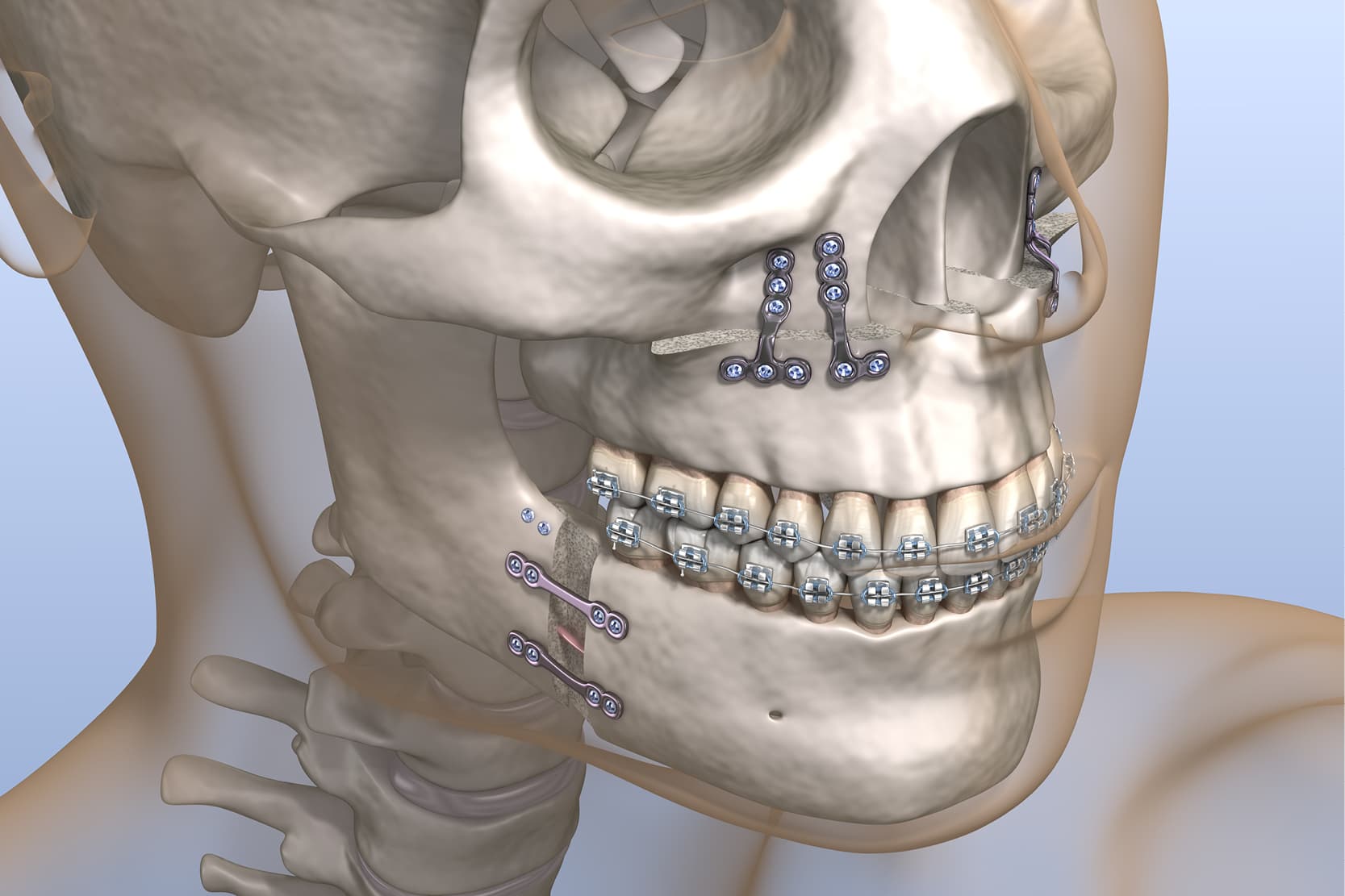

Pre-surgical orthodontics and orthognathic surgery: rationale, indications and protocols

In a world of dentistry that is increasingly minimally invasive, where we try to minimise patient intervention, orthognathic surgery and pre- or post-surgical orthodontics seem like obsolete topics.

However, there is a range of indications for these treatments, where orthodontic problems are caused by significant skeletal deformities, thereby requiring surgery.

Maxillary surgery: from its origins to the current approach

Orthognathic surgery originated about a hundred years ago, but it was only in 1957 with the Obwegeser sagittal osteotomy that we entered the modern era of adopting a surgical approach to maxillofacial skeletal deformities. (1)

This approach allows the mandible to be retracted or protracted, ensuring good control of the condylar position.

In the 1970s, maxillary surgery also developed and thanks to LeFort’s studies, theories started to be formulated about the most favourable osteotomic lines for surgical mobilisation of the upper jaw. (2)

These surgical procedures make it possible to raise the maxilla allowing mandibular autorotation, thereby correcting open bite and skeletal hyperdivergences.

At transverse level, the maxilla can be surgically segmented and expanded using rapid palatal expanders. (3-4)

Traditional and pre-surgical orthodontics: an important distinction

The first point to clarify is that traditional orthodontics and pre-surgical orthodontics often have totally divergent objectives. (5)

In fact, exclusively orthodontic camouflage is based on techniques, mechanics and extraction choices that are totally different and often opposite to those that would be implemented if the case had been classified as orthognathic and, therefore, intended for maxillofacial surgery.

Rationale for orthognathic surgery

What is the rationale for orthognathic surgery nowadays?

There are considerations based on aesthetics, function, stability and treatment time that make surgery the treatment of choice. (6)

Aesthetics

Orthognathic surgery should be considered whenever satisfactory alignment of the dental arches would result in clearly worsening the overall facial aesthetics. For example, retracting the maxillary frontal group to reduce the overjet in a case of mandibular retrusion would inevitably result in creating an unsightly biretruded profile. (7)

Function

If a functional problem cannot be resolved through orthodontic treatment alone because the underlying cause is a skeletal problem, the surgical option should be considered. For example, just think of a unilateral cross bite caused by mandibular skeletal asymmetry.

Stability

In the case of some orthodontic problems with an underlying skeletal problem, such as an open bite in a context of skeletal hyperdivergence, orthodontics alone is viewed as a tool which is not very effective and unlikely in the long term to provide stability required to resolve the malocclusion.

Treatment time

In clear-cut surgical cases, a combined surgical-orthodontic treatment turns out to be faster than performing an exclusively orthodontic camouflage. (5)

Objectives and techniques of orthodontic treatment

The purpose of orthodontic treatment must be to prepare the arches for their future surgical relocation once they are completely mobilised.

For this reason, it is more important to work at the level of the single arch rather than considering both arches in occlusion; complete resolution of crowding, orthodontic management of the curve of Spee and transversality are key steps in good pre-surgical orthodontics.

Often, during pre-surgical orthodontics, the only action taken is to decompensate an occlusal pattern which was compensated and did not represent the real severity of the malocclusion at skeletal level. In skeletal class III, for example, upper incisors are often observed to be labially inclined and lower incisors to be lingually inclined; this clinical scenario is an occlusal compensation typical of a skeletal malocclusion and, with a view to a surgery capable of repositioning the bony bases, the objective of orthodontics is to totally decompensate this pattern.

In orthognathic planning it is essential to decide in advance where and how the teeth are to be positioned at the anteroposterior, vertical and transverse levels. In fact, the incisors are the true anteroposterior positional guide for the surgeon.

It is also not beneficial to expend valuable time trying to achieve perfect alignment and aesthetics in the pre-surgical orthodontic phase. Only after surgery, when the occlusion is corrected, will it be appropriate to focus on the finishing process and final aesthetic look at orthodontic level. (8)

Impressions, casts and pre-surgical records

Once the pre-surgical orthodontic objective has been achieved, impressions are taken and study casts are made.

A full thickness stabilising arch is left for at least 3-4 weeks to passivate the arches.

Pre-surgical records are taken:

- Orthopantomography;

- Lateral teleradiography;

- Study casts;

- Intra and extraoral photographs.

A posteroanterior X-ray of the skull is also often taken, especially in cases of asymmetry.

These records allow the surgeon to study the intervention that will be performed, to check the harmony of the arches once repositioned, to decide where to perform the osteotomic lines, how to segment the maxilla and how many millimetres, for example, to advance the mandible.

Post-surgical phase and final considerations

After the operation, with a period of elastic fixation and a liquid diet, the function is gradually regained and in 6-8 weeks the patient is again able to fully chew.

Post-surgical orthodontics is designed to apply the aesthetic finishing touch and should not last more than 4-6 months.

References

- Trauner R, Obwegeser H. The surgical correction of mandibular prognathism and retrognathia with consideration of genioplasty. I. Surgical procedures to correct mandibular prognathism and reshaping of the chin. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1957;10:677–689.

- LeFort R. Etude experimentale sur les fractures de la machoire superieure. Revue Chirurgicale 1901;23:8.

- Bailey LJ, White RP, Proffit WR, Turvey TA. Segmental LeFort I osteotomy for management of transverse maxillary deficiency. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;55:728–731.

- Silverstein K, Quinn PD. Surgically assisted rapid palatal expansion for management of transverse maxillary deficiency. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;55:725–727.

- Sabri, R. (2006). Orthodontic objectives in orthognathic surgery: state of the art today. World journal of orthodontics, 7(2).

- Sinclair PM. Orthodontic considerations in adult surgical orthodontic cases. Dent Clin North Am 1988;32:509–528.

- Ackerman JL, Proffit WR. Soft tissue limitations in orthodontics: Treatment planning guidelines. Angle Orthod 1997;67:327–336.

- Woods MG, Wiesenfeld D. A practical approach to presurgical orthodontic preparation. J Clin Orthod 1998;32:350–358.

Would you like more information about Zhermack Dental products and solutions?

Contact us

Zhermack SpA has been one of the most important producers and international distributors of alginates, gypsums and silicone compounds for the dental sector for over 40 years. It has also developed solutions for the industrial and wellbeing sectors.

Zhermack SpA - Via Bovazecchino, 100 - 45021 Badia Polesine (RO), Italy.

Zhermack SpA has been one of the most important producers and international distributors of alginates, gypsums and silicone compounds for the dental sector for over 40 years. It has also developed solutions for the industrial and wellbeing sectors.

Zhermack SpA - Via Bovazecchino, 100 - 45021 Badia Polesine (RO), Italy.