Bruxism is a parafunctional activity that has always been of great interest to dentists as many of its effects are intraoral though most of its causes are to be sought extraorally.

Bruxism can easily lead to the destruction of tooth tissue, the breakage of reconstructions or prosthetic rehabilitations, the exacerbation of temporomandibular disorders, and to tension headaches and disturbance of a partner’s sleep by teeth grinding noises at night. (1)

Bruxism can be defined as a diurnal or nocturnal parafunctional activity that includes the clenching and grinding of teeth. While sufferers from diurnal bruxism are aware of clenching their teeth, nocturnal bruxism causes unconscious stereotyped movements during sleep, typically clenching or grinding. (1, 2)

A diagnosis of bruxism cannot be made exclusively on the basis of tooth wear (wear veneers), as the parafunctional activity could well have occurred long before wear is noticed by the dentist. (1)

Aetiology (3)

As a parafunctional activity, nocturnal bruxism may be caused by many factors, and various theories have been put forward over the years.

Peripheral factors

The cause was initially thought to be purely mechanic, and that the patient’s occlusion in some way favoured or disfavoured this parafunction. Precontact or occlusal interference were believed to encourage phenomena of nocturnal grinding. (4) This correlation was later refuted by various studies and it was shown instead that the patient’s occlusal pattern had nothing to do with the onset of bruxism. (1, 5)

Stress and psycholgical factors

Stress and other psychological factors have been considered important in the aetiology of bruxism. Some early studies demonstrated increased masticatory muscle activity during sleep during periods of severe stress. Other research, however, showed that this association was only valid in a small percentage of the population. It is well established, however, that adults and children who are aware of grinding their teeth are typically more anxious, aggressive and hyperactive individuals. (6)

The current hypothesis

The most recent theory concerning the causes of bruxism is based on the role of the autonomic central nervous system in the genesis of oromandibular activity during sleep.

The role of neurotransmitters

The first evidence that teeth grinding could be linked to a neurotransmitter came from a case report in which a patient suffering from Parkinson’s disease was prescribed levodopa, a precursor of catecholamine, to treat teeth grinding. (7)

Hypothesising a causal role for noradrenaline, various studies were carried out into the use of clonidine and propanolol (8, 9). It was seen that clonidine, in addition to reducing the sympathetic cardiac activity that precedes RMMA (rhythmic masticatory muscle activity), also reduced attacks of nocturnal bruxism. Clonidine, however, is not indicated for the treatment of bruxism as it induces severe morning hypotension.

Micro-arousal during sleep and motor activation

Studies have shown that episodes of nocturnal bruxism generally last from 3 to 10 seconds and are associated with an increase in cerebral and cardiac activity that causes a rapid increase in heart rate (tachycardia) (10). Transient increases in cerebral and cardiac activity and muscle tone occur at every hour during sleep, causing between 8 and 15 micro-arousals (1).

Most episodes of bruxism arise during light, non-REM sleep, while only 10% occur during REM phases.

Signs and symptoms (11)

Symptoms of bruxism include:

- Teeth grinding accompanied by the characteristic noise

- Temporomandibular joint pain

- Masticatory and cervical muscle pain

- Localised temporal headaches in the morning

- Hypersensitivity of the teeth

- Excessive mobility of the teeth

- Tiredness and poor sleep quality

Signs of bruxism include:

- Abnormal tooth wear (wear veneers)

- Scalloped tongue

- Linea alba along the occlusal plane

- Receding gums

- Presence of maxillary and mandibular tori

- Increased muscular activity (recordable by polisomnography)

- Hypertrophy of masseter muscles

- Reduced saliva flow

- Broken teeth and/or reconstructions and/or prosthetic rehabilitations

- Restriction in mouth opening

Treatment (3)

There is currently no effective treatment for bruxism. Available treatments only reduce the potentially damaging effects of the parafunction.

Approaches always require behavioural changes to help the patient relax. Typically, the patient’s diet should be modified, the patient educated in the causes of bruxism and taught various relaxation techniques. It must, however, be pointed out that there is no scientific evidence in support of any one particular technique.

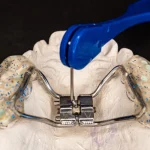

The most common treatment today involves the use of upper or lower arch bite plates to eliminate interference, protect the teeth against grinding and relax the masticatory muscles. To produce a bite plate, the dentist must start by taking an impression, which needs to be accurate and to include all teeth without distortion in order to prevent teeth moving accidentally. In many cases, to ensure that the bite plate is accurate, the dental technician also has to be provided with a bite registration of the plate, especially for thickness. There is no evidence, however, that these devices actually cure bruxism. Basically, the bruxism will continue, but the bite plate will prevent its most destructive effects on the masticatory system.

Certain pharmacological trials of bruxism treatments involving the central nervous system have given promising results. Drugs that act on the central nervous system have proved effective in reducing the frequency of episodes of bruxism. Nevertheless, a limited amount of supporting literature and the risk of unknown side effects currently make a pharmacological approach to bruxism unattractive.

To sum up, as things stand, following a correct diagnosis of bruxism, patients should receive behavioural help to reduce the frequency of episodes and a bite plate should be used to prevent the damage potentially caused to the masticatory system by this parafunction.

References

- Lavigne, G. J., Khoury, S., Abe, S., Yamaguchi, T., & Raphael, K. (2008). Bruxism physiology and pathology: an overview for clinicians. Journal of oral rehabilitation, 35(7), 476-494.

- De Laat A, Macaluso GM. Sleep bruxism as a motor disorder. Mov Disord. 2002;17(suppl.):S67–S69.

- Klasser, G. D., Rei, N., & Lavigne, G. J. (2015). Sleep bruxism etiology: the evolution of a changing paradigm. J Can Dent Assoc, 81, f2.

- Ramfjord SP. Bruxism, a clinical and electromyographic study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1961;62:21-44.

- Lobbezoo F, Naeije M. Bruxism is mainly regulated centrally, not peripherally. J Oral Rehabil. 2001;28(12):1085-91.

- Laberge L, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Montplaisir J. Development of parasomnias from childhood to early adolescence. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt1):67-74.

- Winocur E, Gavish A, Voikovitch M, Emodi-Perlman A, Eli I. Drugs and bruxism: a critical review. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17(2):99-111.

- Huynh N, Kato T, Rompré PH, Okura K, Saber M, Lanfranchi PA, et al. Sleep bruxism is associated to micro-arousals and an increase in cardiac sympathetic activity. J Sleep Res. 2006;15(3):339-46.

- Huynh N, Lavigne GJ, Lanfranchi PA, Montplaisir JY, de Champlain J. The effect of 2 sympatholytic medications — propranolol and clonidine — on sleep bruxism: experimental randomized controlled studies. Sleep. 2006;29(3):307-16.

- Reding GR, Zepelin H, Robinson JE Jr, Zimmerman SO, Smith VH. Nocturnal teeth-grinding: all-night psychophysiologic studies. J Dent Res. 1968;47(5):786-97.

- Murali, R. V., Rangarajan, P., & Mounissamy, A. (2015). Bruxism: Conceptual discussion and review. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences, 7(Suppl 1), S265.

Do you want more information on Zhermack Dental products and solutions?

Contact Us

Zhermack SpA has been one of the most important producers and international distributors of alginates, gypsums and silicone compounds for the dental sector for over 40 years. It has also developed solutions for the industrial and wellbeing sectors.

Zhermack SpA - Via Bovazecchino, 100 - 45021 Badia Polesine (RO), Italy.

Zhermack SpA has been one of the most important producers and international distributors of alginates, gypsums and silicone compounds for the dental sector for over 40 years. It has also developed solutions for the industrial and wellbeing sectors.

Zhermack SpA - Via Bovazecchino, 100 - 45021 Badia Polesine (RO), Italy.