Taking an impression from an adult is normally a routine procedure for an experienced dentist. In the vast majority of cases it is stressful neither for the dentist nor the patient unless the latter has a particularly strong pharyngeal reflex. In the worst hypothesis, a second impression may have to be taken if the first proves defective.

When the patient in the chair is a young child, however, matters are completely different.

But let us start from the beginning. When is it necessary to take an impression from a child?

When do you take an impression from a child

In most cases, the need for a dental impression derives from orthodontic problems. Sometimes, an orthodontist may detect the start of malocclusion when a child is as young as four years old. (1) (2) At present, the tendency is to await the complete eruption of the first permanent molars, which normally occurs around the age of 6, or at least to wait for the presence of early mixed dentition. (3)

In the field of orthodontics, an impression may be required for two reasons: to produce a fixed or mobile appliance and/or to produce a medical or legal record. In either case, impressions used to produce stone models should represent snapshots of the start and the end of the orthodontic treatment.

In rare cases, impressions need to be taken from very young children.

While waiting for a surgical solution, children affected by labiopalatoschisis sometimes require a palatal obturator to prevent the regurgitation of food into the nasal cavity. In such cases, an impression of the infant’s palate may be required as early as a few days after birth. (4)

The materials and techniques used to obtain such an impression vary significantly from one case to another and it is difficult to identify any standard protocol.

Children affected by ectodermal dysplasia often display a certain degree of oligodontia or sometimes even anodontia. These cases require a prosthetic-orthodontic solution to facilitate the child’s feeding and prosthetic expansion screws to encourage correct arch development in view of future rehabilitation. (5) (6) Materials and techniques vary greatly on a case by case basis with these patients too.

Now let us examine another aspect: how do you take an impression from a child?

How do you take an impression from a child

Excluding rare cases of syndromic and congenital malformations, the procedure for impression taking in children has been widely discussed in the literature. As with all invasive procedures carried out on children, impression taking requires particular attention to the child’s psychological attitude and behaviour, especially in certain cases.

As illustrated by the AAPD (American Association of Pediatric Dentistry), various factors need to be assessed to predict a child’s behaviour. (7) The dental practice must be able to assess young patients’ levels of anxiety and fear, determine whether such anxiety is the result of previous unpleasant or painful experiences, and foresee how the child might react to a certain stimulus. Understanding the patient’s psychology is essential to identifying the best procedure. Another aspect to consider when dealing with very young children concerns the parents. Those who pay little attention to oral hygiene or who are frightened of dental treatment often project those attitudes on to their children.

If the young patient refuses to collaborate, it is often best to fix another appointment to avoid creating additional trauma and making future cooperation even more difficult. Focusing on the impression taking procedure itself, there are various ways to reduce anxiety in young patients and limit the pharyngeal reflexes (8) that are often the most challenging reactions to manage.

Various techniques to reduce anxiety in young patients

The pharyngeal or gag reflex exists to prevent the ingress of foreign bodies into the pharynx, larynx and trachea: normally, it diminishes slowly over the first four years of life. Accentuated pharyngeal reflexes, however, continue to exist in 28.5% of children between the ages of four and twelve. The aetiology of the pharyngeal reflex may be somatic or psychological. It can be triggered by sensory stimuli (tactile, auditory, visual or olfactory). The tactile and olfactory stimuli produced during impression taking can easily cause this reflex. If the problem persists, it becomes difficult if not impossible to obtain a sufficiently accurate impression because the reflex causes spasmodic and uncoordinated movements in the soft palate, abdominal walls, intercostal muscles and diaphragm.

The pharyngeal reflex is exacerbated by a state of anxiety and previous negative experiences of dental treatments. Over the years, various strategies have been proposed to contain this reaction: relaxation techniques, systemic desensitisation, pharmacological approaches, local anaesthesia, conscious sedation, acupuncture and even hypnosis. Impressions of the upper arch are normally the ones that trigger the pharyngeal reflex. The medullary centre of the pharyngeal reflex is partly controlled by the cerebral cortex through neural networks: the reflex can therefore be partly checked by distracting the patient.

Various techniques have been experimented over the years: getting the child to breathe through the nose while beating time with the hand or getting him to raise an arm or leg and keep it raised throughout the procedure. All these tricks have proven effective but there is no evidence that any one is any more effective than another. The important thing is to distract the attention of the young patient from the procedure being performed.

Another interesting point is the sequencing of procedures. (9) While adults generally prefer to get the most troublesome or painful procedures over with first and finish the session with the least unpleasant procedures, the opposite rule applies to children: sessions should start with gentle procedures and build up to the most unpleasant at the end. In the case of children, therefore, the bottom arch impression should always be taken first.

The best materials for impression taking in children

Now let us look at the most suitable materials for impression taking in children. The use of fast and extra-fast materials minimises time in mouth and therefore limits the pharyngeal reflex and the discomfort experienced during impression taking. These materials should therefore be chosen when treating children.

Scent is another important characteristic: choose a pleasantly scented material to avoid exacerbating the pharyngeal reflex with disagreeable olfactory stimuli. Another point worth considering is that, unlike those for fixed prostheses, impressions for these treatments do not demand a high level of accuracy as the appliances concerned will not remain in the mouth for many years, but only for the duration of therapy. Any gap between the appliance and the surface of the teeth can be filled in with cement.

Because of these considerations, alginates are the materials most commonly used to take orthodontic impressions in children. (10) Most alginates are inexpensive, set rapidly, are attractively coloured and have a pleasant scent.

Taking an impression from a child: a summary

To sum up, impression taking in children requires certain strategies.

First of all, the child needs to be assessed from a psychological and behavioural point of view, and secondly the whole team needs to avoid creating situations likely to cause anxiety. From the moment the child enters the chair, he should be told exactly what the next step in the treatment is. Once his cooperation has been ensured, every attempt should be made to distract him by asking questions, getting him to perform certain movements and taking the bottom impression while continuing to distract his attention.

Time is the most important aspect of impression taking in children. The sooner the procedure can be completed, the better it is. Fast and extra-fast materials should therefore be used. Pleasantly scented materials should also be preferred when treating children, since olfactory stimuli contribute to triggering the pharyngeal reflex. With the bottom impression taken, move on to the upper arch, distracting the patient at all times and keeping him as upright as possible.

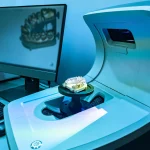

The Zhermack solution for impression taking in children

The material that Zhermack recommends for impression taking in children is Orthoprint. Orthoprint is an extra-fast alginate with a vanilla scent and has been recommended for orthodontic applications by 97% of users (11). The key characteristics that make Orthoprint ideal for paedodontic and orthodontic applications are its limited time in mouth (which makes it easily tolerated by all patients (11)), a vanilla scent that children appreciate (12)) and good elasticity.

Bibliography

(1) Woon, S. C., & Thiruvenkatachari, B. (2017). Early orthodontic treatment for Class III malocclusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 151(1), 28-52.

(2) LINDNER, A. (1989). Longitudinal study on the effect of early interceptive treatment in 4‐year‐old children with unilateral cross‐bite. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 97(5), 432-438.

(3) Lippold, C., Stamm, T., Meyer, U., Végh, A., Moiseenko, T., & Danesh, G. (2013). Early treatment of posterior crossbite-a randomised clinical trial. Trials, 14(1), 1-10.

(4) Chandna, P., Adlakha, V. K., & Singh, N. (2011). Feeding obturator appliance for an infant with cleft lip and palate. Journal of Indian Society of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, 29(1), 71.

(5) Tarjan, I., Gabris, K., & Rozsa, N. (2005). Early prosthetic treatment of patients with ectodermal dysplasia: a clinical report. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, 93(5), 419-424.

(6) Ou-Yang, L. W., Li, T. Y., & Tsai, A. I. (2019). Early prosthodontic intervention on two three-year-old twin girls with ectodermal dysplasia. European journal of paediatric dentistry, 20(2), 139-142.

(7) https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/policies_guidelines/i_overview.pdf

(8) Dixit, U. B., & Moorthy, L. (2021). The use of interactive distraction technique to manage gagging during impression taking in children: a single-blind, randomised controlled trial. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry, 22(2), 219-225.

(9) Kaakko, T., Horn, M. T., Weinstein, P., Kaufman, E., Leggott, P., & Coldwell, S. E. (2003). The influence of sequence of impressions on children’s anxiety and discomfort. Pediatric dentistry, 25(4), 357-364.

(10) Staley, R. N., & Reske, N. T. (2011). Essentials of orthodontics: diagnosis and treatment. John Wiley & Sons.

(11) Key-Stone Italia survey, 2019

(12) Zhermack Italy and Germany survey, 2019

Do you want more information on Zhermack Dental products and solutions?

Contact us

Zhermack SpA has been one of the most important producers and international distributors of alginates, gypsums and silicone compounds for the dental sector for over 40 years. It has also developed solutions for the industrial and wellbeing sectors.

Zhermack SpA - Via Bovazecchino, 100 - 45021 Badia Polesine (RO), Italy.

Zhermack SpA has been one of the most important producers and international distributors of alginates, gypsums and silicone compounds for the dental sector for over 40 years. It has also developed solutions for the industrial and wellbeing sectors.

Zhermack SpA - Via Bovazecchino, 100 - 45021 Badia Polesine (RO), Italy.